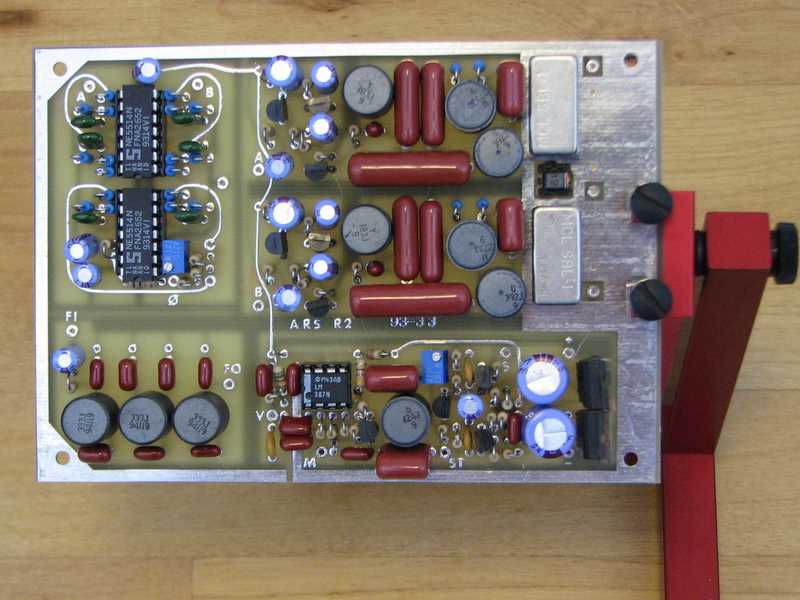

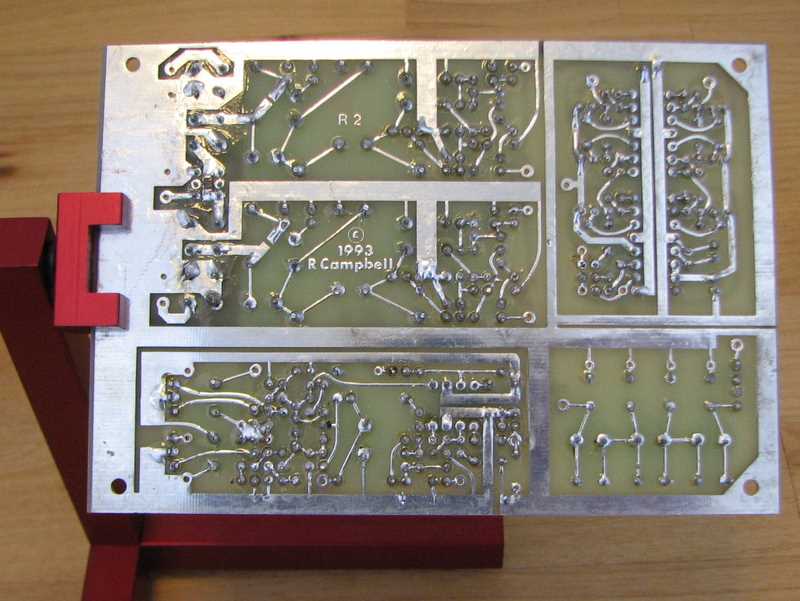

Crunch time at work has been limiting my basement tinkering, but I recently found time to work on my R2 receiver a bit more. It is pulling excessive bias current, which had me scratching my head. The audio power amplifier bias is supposed to be adjusted so that the whole board pulls 100 mA, but it’s taking 120 mA even with the bias pot set to its minimum. After double-checking all of the component values and verifying all of the bias voltages on the board, I was left scratching my head. Then I remembered the age of the kit. Even while building it, I had doubts about the electrolytic capacitors…

This R2 kit includes 15 Panasonic Z-series electrolytic capacitors. Aluminum electrolytic caps are good at one thing: Lots of capacitance at a low cost. In nearly every regard, they have inferior performance, with high equivalent series resistance (ESR), inductance (ESL), and, yes, a short lifetime. I’m not sure exactly how to translate the lifetime specifications for electrolytics to room temperature storage, but the rule of thumb tends to be that they can tolerate 5 years on the shelf, after which they require a “reforming” procedure. Reforming them at that point can get them to last another 5 years or so. After that, figure that they are shot. Old electrolytic capacitors can have excessive leakage current. In extreme cases, this current is enough to heat them up excessively and they go bang! The capacitors on this board are old enough to vote. Maybe one or more of them are to blame for the extra milliamps.

I had a little trouble finding the perfect capacitors, but then I was looking for performance at least as good as the original. This was perhaps foolish, because I couldn’t find data on the Z-series caps. Panasonic discontinued them in 2000. In lieu of further information, I arbitrarily went for high-quality models from a favorite manufacturer. In some cases, these were nearly double the price of the cheapest options, a breathtaking 23 cents versus 12 cents, quantity one. Seriously, replacements for all of the caps cost all of $2.85, including a few spares for good measure.

My one mistake so far is to forget about the T2 transmitter. If the R2’s capacitors are bad, the T2’s surely are as well. Maybe the spares I bought will end up there.

Troubleshooting is half the fun of this stuff. Who needs sudoku when you can puzzle out a misbehaving circuit?